How Pre-IPO Markets Failed Investors

One of the most significant failures in modern capital markets

The pre-IPO market has always been stacked against retail investors.

Access to private shares typically means $100k+ minimums, inflated secondary pricing, year-long lockups, and layers of fees. For retail investors, this exclusion is especially unfortunate given how the market has evolved:

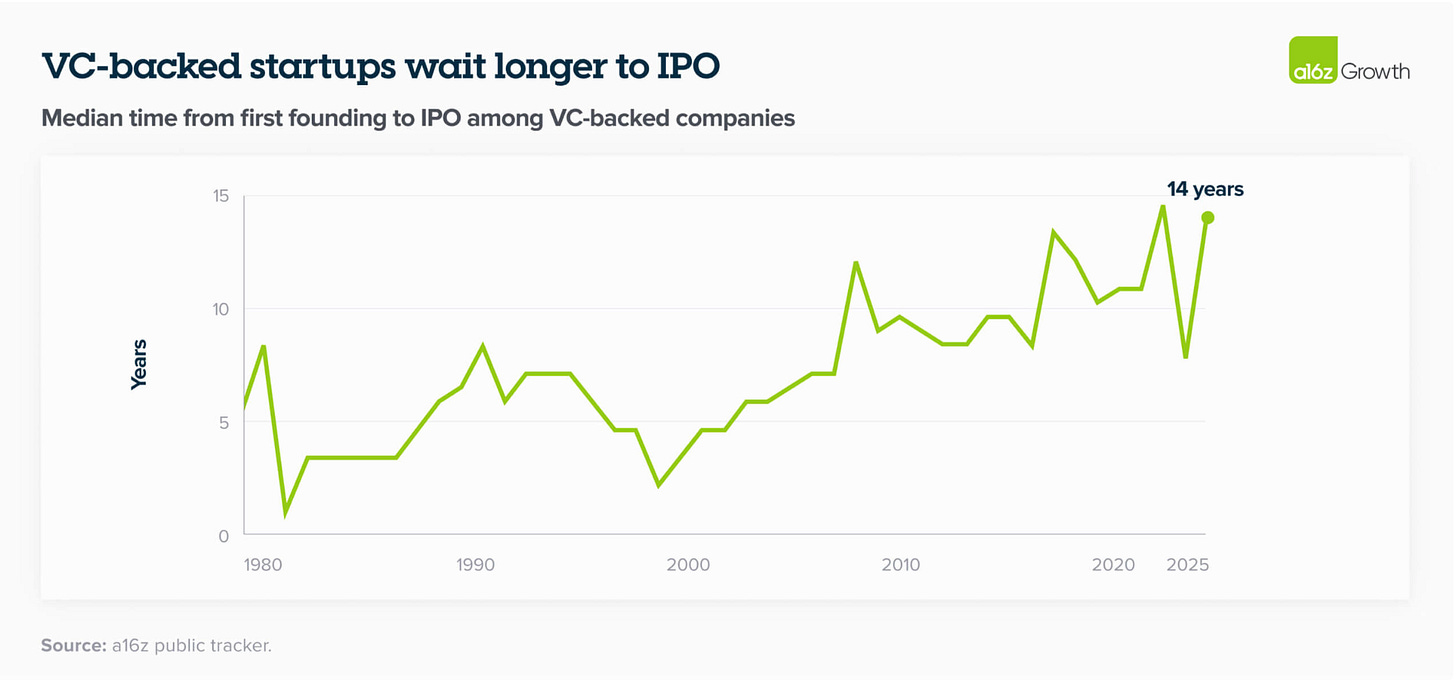

The median time to IPO has roughly doubled since the late 90s, stretching from ~5 years to 14 years today

The median company in the 2014–2019 IPO cohort generated 80%+ of its market cap after becoming public

More recent IPO cohorts now capture over 50% of their eventual market cap while still private

The result is a clear mismatch: value creation has moved decisively into private markets, but the price discovery and liquidity infrastructure has not followed.

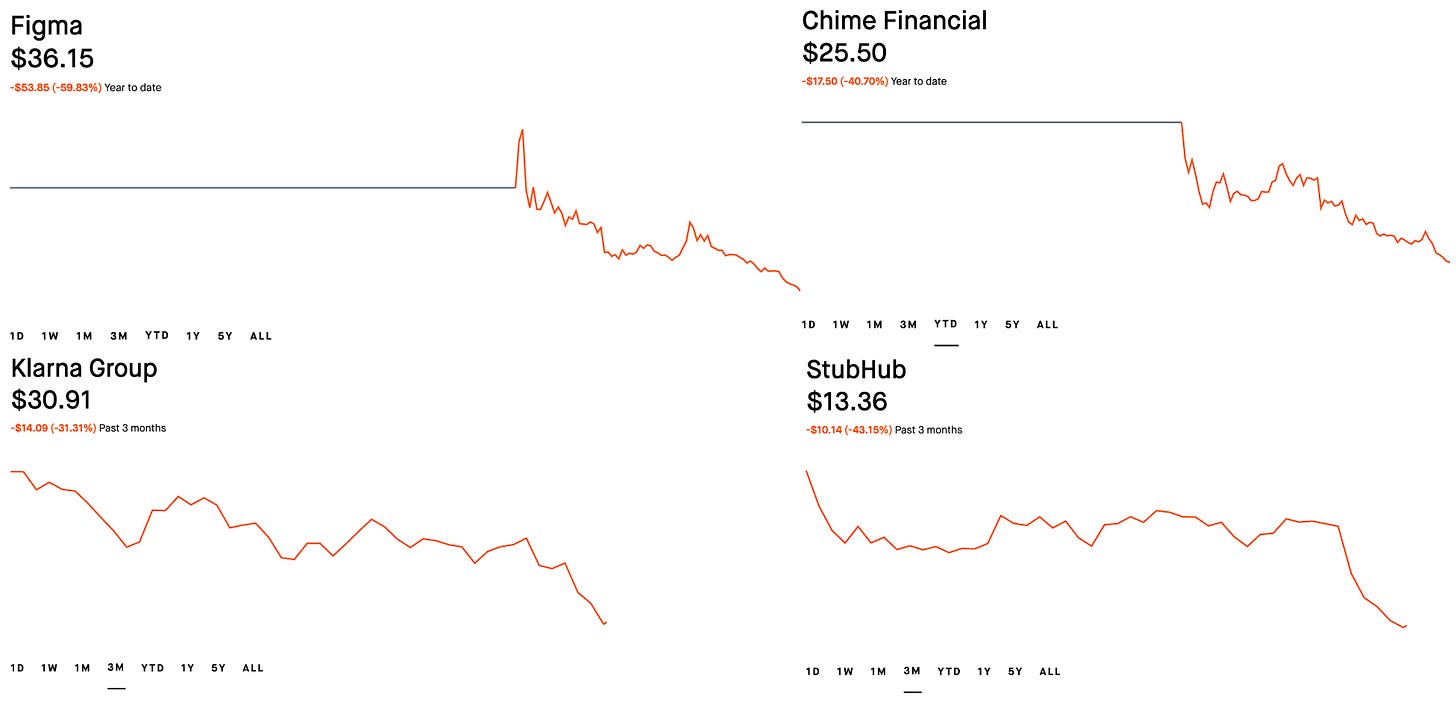

Across much of the 2025 IPO cohort, public markets have served more as liquidity and de-risking venues than as sites of meaningful value creation, with current prices often sitting ~50% below the initial opening.

Nonetheless, with the IPO window reopening this year, there has been a renewed push in crypto to “democratize” private markets through tokenization and perps. In practice, however, most of these efforts are building tradable wrappers on top of a market that remains fundamentally broken. It is data-poor, illiquid, and structurally fragmented.

The core problem is simple. Pre-IPO shares lack a real spot market with depth, reliable execution, and credible price discovery. Without that foundation, anything built on top is purely cosmetic.

There are two reasons this market has never developed:

First, private shares live directly on a company’s cap table and require issuer consent to transfer. SpaceX is not adding a $150 buyer to its cap table, and even large institutional transactions are routinely rejected for strategic, regulatory, or reputational reasons.

Second, under SEC Rule 144, most resales of private company stock require a minimum 12-month holding period before shares can be legally sold.

TL;DR: no free transferability + no inventory velocity = no order book.

To understand why this gap persists, it’s worth examining how today’s pre-IPO market is actually structured and who it is designed to serve.

Pre-IPO Landscape

The pre-IPO market can be broadly categorized into two segments: institutional-focused and retail-focused platforms. Institutional venues, namely Nasdaq Private Markets and Forge, dominate the market with >90% market share.

1. Broker/Marketplace Model

Overview: This is the primary mechanism through which institutional capital accesses pre-IPO equity.

How it works: Forge operates a broker-dealer marketplace. Most transactions are intermediated by brokers who source blocks of shares from employees, funds, or early investors. Instead of a live public order book, brokers typically match institutional buyers with sellers in large negotiated block trades.

Pros:

No balance sheet risk – Platforms don’t warehouse inventory

Direct ownership – Buyers end up with actual company shares, no derivatives or SPV models

Minimal counterparty risk – Trades are executed via regulated broker-dealers, with escrow and company transfer approval processes

Scalability/Access – Because brokers cultivate relationships with funds, banks, and issuers, they can source large blocks and give buyers exclusive access to deals with size

Cons:

Opaque pricing – Transactions are privately negotiated, often at wide spreads vs fair value. And orders are often re-quoted

Slow settlement – Typical transactions take 6-8 weeks

High fees – Broker commissions (2–5%+) eat into both buyer and seller proceeds

Retail excluded – High minimums (often $100K+)

Company approval bottleneck – Issuers can block or delay transfers. And >50% of transactions are usually rejected

2. Company-Sanctioned Liquidity Programs

Overview: These programs represent the most orderly and issuer-aligned form of pre-IPO liquidity.

How it works: Platforms like Nasdaq Private Market (NPM) and Carta Liquidity run issuer-approved tender offers, buybacks, or secondary programs. These aren’t continuous markets but structured events, usually once or twice a year, tied to major financings. After board and legal approval, a 2–6 week window opens where eligible shareholders can sell, with the company aggregating bids, setting a clearing price, and executing in bulk.

The pros and cons are nearly identical to the above model, the key difference is that sanctioned programs are structured, time-bound events with guaranteed company participation, lower fees, and cleaner cap table management. Importantly, even Nasdaq does not describe NPM as an exchange. It functions closer to a cap-table administration, compliance, and transaction-coordination platform.

The structural frictions embedded in institutional pre-IPO platforms have, in turn, driven the emergence of retail-focused offerings built around SPV-based access models.

3. Inventory/Principal Model

Overview: This model offers retail investors simplified, immediate access to pre-IPO equity by having the platform act as principal, acquiring shares and reselling fractionalized exposure.

How it works: The platform acquires pre-IPO shares from employees, early investors, or funds, assumes inventory risk, and then resells fractionalized interests to retail investors. Examples include platforms such as Linqto.

Pros:

Immediate execution: No multi-week negotiation or issuer-run liquidity window

Low minimums: Fractionalization enables retail participation

Operational simplicity: The platform handles sourcing, custody, and transfer logistics

Cons:

Balance sheet risk: Platforms assume principal exposure and inventory risk, reducing scalability

High effective pricing: Markups and fees are embedded in the offer price

Limited investor protections: Retail investors hold indirect exposure rather than direct shares

No secondary liquidity: Positions are typically illiquid until an IPO, acquisition, or platform-facilitated exit

Regulatory complexity: Structures often operate near the edge of securities and transfer-restriction regimes

4. SPV Aggregator Model

Overview: This model enables retail-accredited investors to access pre-IPO equity by pooling capital into an SPV that collectively acquires a secondary block of shares.

How it works: Multiple retail accredited investors are pooled into an SPV, which collectively purchases a secondary block of shares. Examples include platforms such as EquityZen and AngelList.

Unlike the inventory/principal model, SPV aggregators do not warehouse shares or assume balance sheet risk. Pricing risk is borne entirely by investors, and access is gated by successful capital aggregation rather than platform inventory. Beyond the absence of platform balance-sheet risk, most of the remaining tradeoffs mirror those of the inventory/principal model.

To summarize, we can segment the landscape as:

Broker/Marketplace (institutional matchmaker)

Company-Sanctioned (issuer-led)

Inventory/Principal (retail reseller)

SPV Aggregator (pooled retail)

So we are left with:

The Institutional route that is fundamentally inaccessible to retail OR the retail route which is littered with poor pricing, high fees, no secondary market, and weak investor protections.

But can tokenization or perps solve these issues?

Why pre-IPO perps are too early

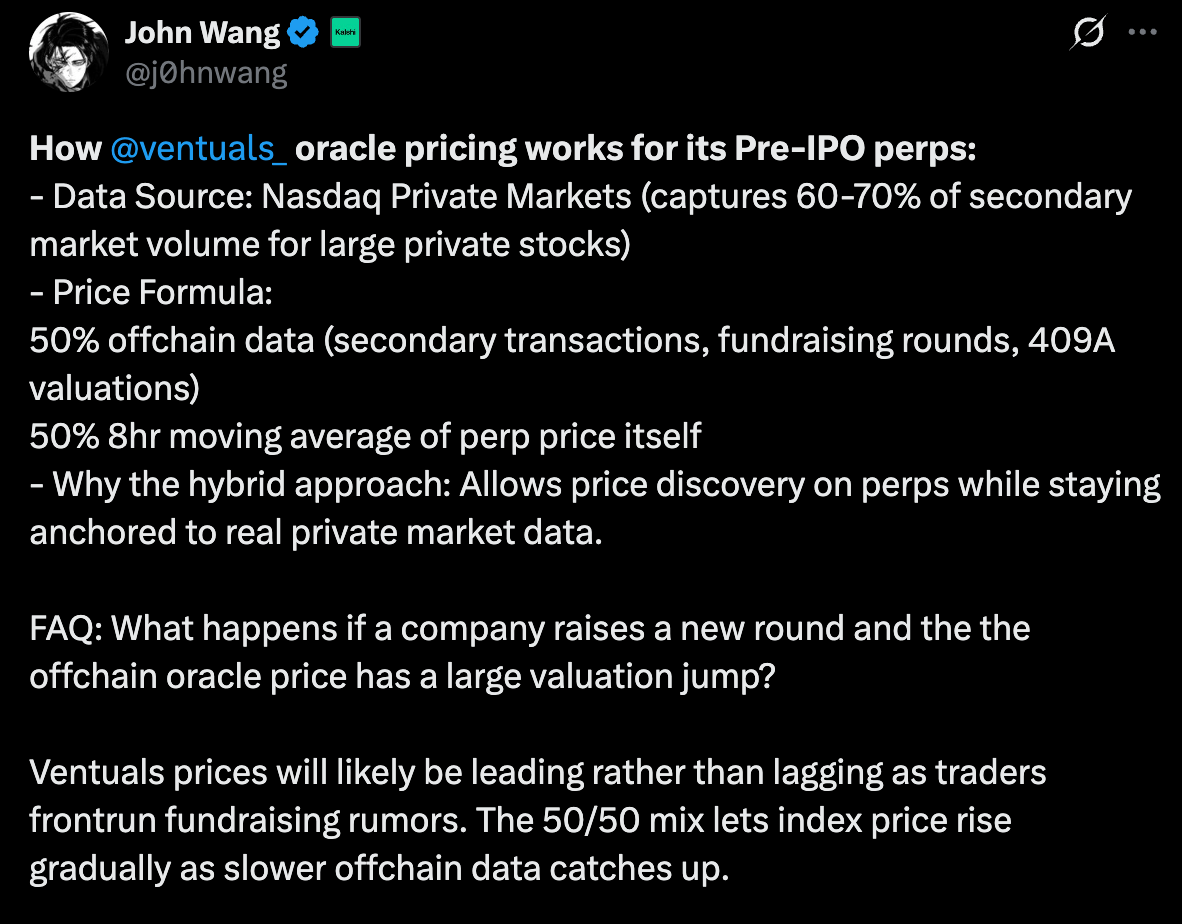

Launching a perp DEX is table stakes post HIP-3. The real challenge lies in the oracle, specifically where and how reliable pricing data is sourced.

As we covered above, the pre-IPO spot market is slow, opaque and predominantly broker driven, meaning there are no real-time pre-IPO price feeds in existence.

Per John, Ventuals, a new pre-IPO perps platform, is using a combo of offchain data (NPM price feeds, 409As, etc.) + the 8hr moving average of the perp price itself.

For reference, 409As can be up to 90 days old by the time they’re circulated. More importantly, they are often intentionally deflated to provide favorable Fair Market Values (FMV) for employee stock options; companies want lower valuations here to minimize the tax burden on employees receiving equity compensation. Thus, the resulting price isn’t a fair value of the stock price in the open market, and 409As can often be as low as 1/4th the price of the most recent primary round.

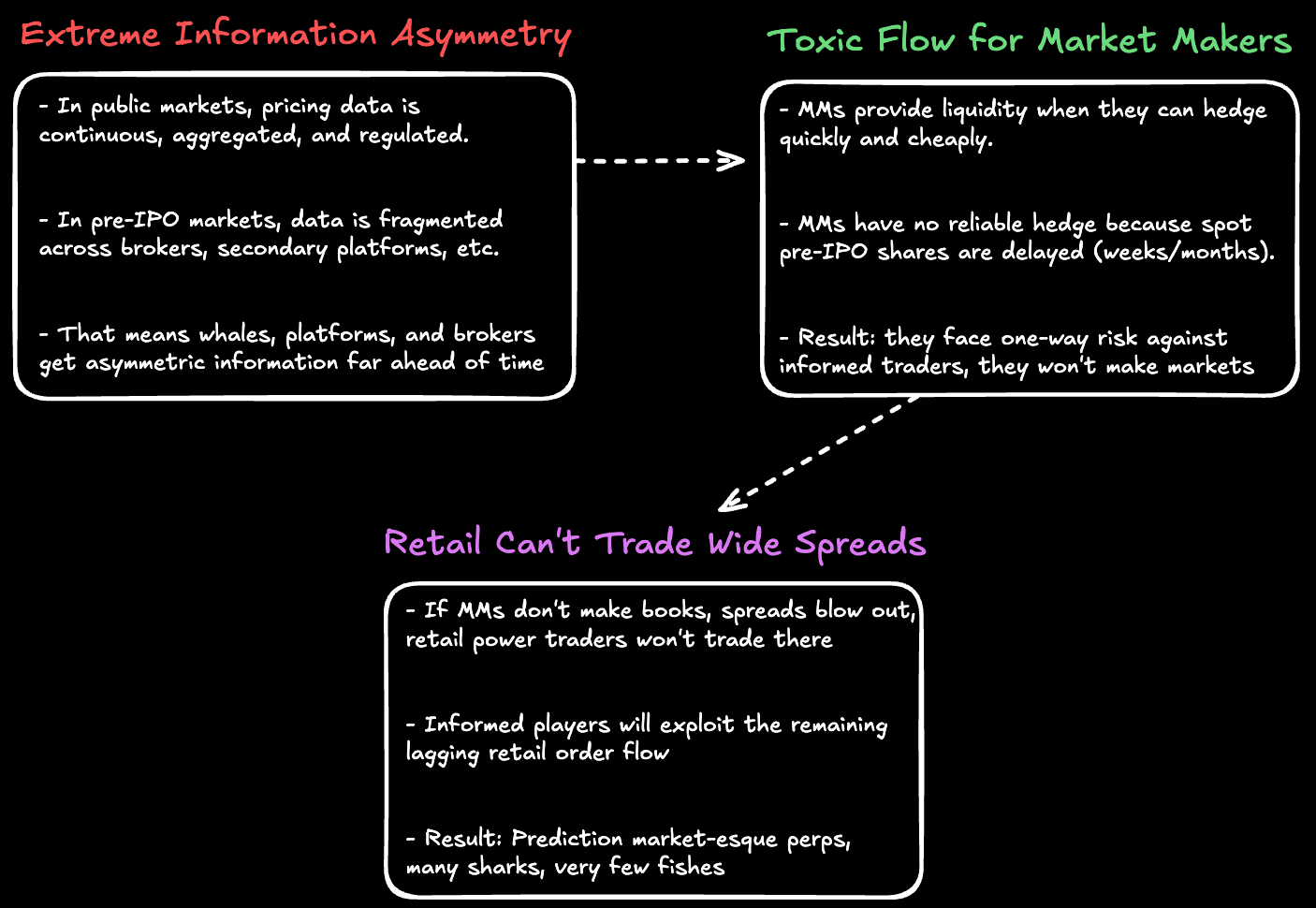

As such, I suspect early pre-IPO perp platforms will behave closer to prediction markets where toxic flow is a feature not a bug. Here’s why:

Put simply, pre-IPO markets attract a high concentration of informed traders: brokers, secondary funds, and platform operators at a minimum. For market makers, this creates a toxic-flow problem with no offsetting hedge, since no real-time spot market exists. The outcome is predictable: market makers don’t quote, spreads widen, and retail loses interest in trading altogether.

Given the data + toxic flow problem with perps, the natural next question is: what if we skip the derivatives layer entirely and just tokenize pre-IPO shares directly?

Why pre-IPO tokenization doesn’t work

There’s two routes to evaluate tokenization: institutional and retail.

Institutional would only happen if the issuer itself decided to natively issue shares onchain. I don’t see that happening in the foreseeable future. And Forge or NPM won’t do it without issuer consent.

The retail route implies either 1) the platform purchases shares via an SPV and resells the tokenized version to retail or 2) the platform pools user funds, purchases private shares, and you receive tokenized shares in your wallet.

In either case, these models fail to address the core constraints that plague the pre-IPO market. Retail platforms must still solve how to source shares at scale without assuming inventory risk, clearly define what investors actually own and whether those claims are bankruptcy-remote, shorten mandatory holding periods, and aggregate sufficient two-sided order flow to support liquidity. Tokenization does not resolve any of these issues. In fact, by relying on SPV-based structures, it often introduces an additional problem: offerings on the same platform can carry materially different fee structures, governance terms, and economic rights, undermining fungibility of shares.

The pre-IPO spot market is the single hardest problem no one’s solved in over a decade.

Tokenization can however add real value once the underlying spot market structure is fixed. But right now it just amplifies bad market structure.

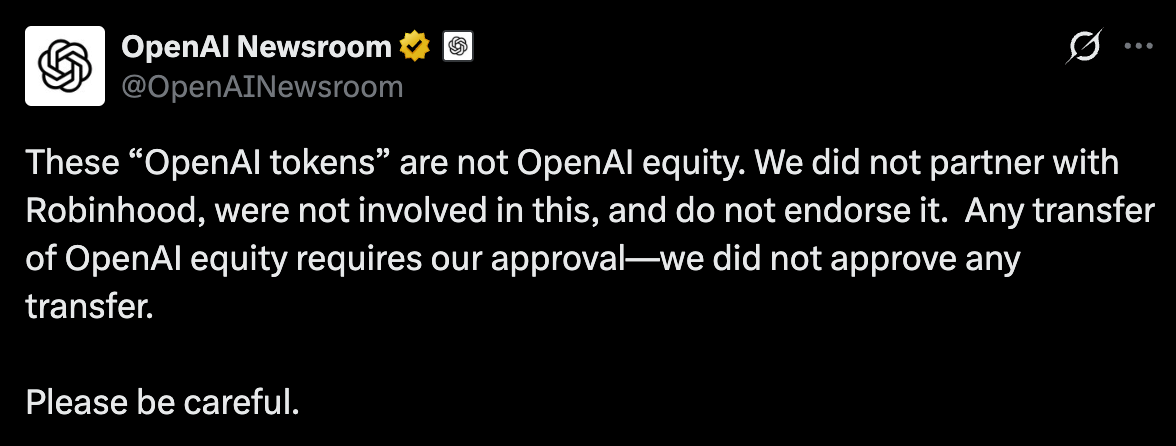

Social Alignment

Further, underlying companies would need to be comfortable with tokenization for the asset class to scale, and right now that seems unlikely.

Tokenizing pre-IPO equities can result in the underlying stock units being voided if it’s perceived by the underlying company to be adversarial to their interests. It’s likely that the end retail purchaser of such tokens would be the last person to know that their capital is at risk in this way.

What is the endgame?

The path to winning starts with building a liquid, real-time spot market. One with low fees, shorter holding periods, and bankruptcy-remote structures as the foundation.

Once daily volumes reach levels that can support meaningful perp open interest across the top private markets, low-leverage perps can be introduced. At that stage, the platform’s own spot market doubles as the live price feed and, more importantly, unlocks real-time liquidity for market makers, laying the groundwork for the deepest and most efficient markets.

Looking ahead, tokenization of private shares could eventually move the spot market fully onchain, enabling the full composability and accessibility of DeFi. But that vision remains at least a few years out, held back by regulatory, structural, and market-driven hurdles.

For too long, retail investors have been locked out of private markets. As companies stay private longer and treat public markets as mere exit liquidity, unlocking liquid access to these assets will stand as one of the most important innovations in modern capital markets.

All views expressed are my own.

Sources:

[1] https://a16z.com/private-markets-new-public-markets

[2] https://www.augment.market/the-power-20 (image)